Gervaciley Júnior: A Guide, a Philosopher, and the Quiet Wisdom of São Tomé and Príncipe

Cartographies of Elsewhere, Dispatch 07, Danuta's Flights

“We shall not cease from exploration, and the end of all our exploring will be to arrive where we started and know the place for the first time.”

~ T.S.Eliot, Four Quartets

“The world is before you and you need not take it or leave it as it was when you came in.”

~ James Baldwin, The Fire Next Time

There are geographies that do not announce themselves with spectacle, but rather disclose their essence through an encompassing stillness, a sensory hush in which presence becomes a form of attention. São Tomé and Príncipe is one such place—not loud, but resonant.

The island breathes with a kind of vegetal insistence. The air is thick with humidity and saturated with scent—waxy leaves, volcanic soil, purple orchids, porcelain roses, crimson hibiscus, and bursts of tree marigold. Formed by fire, the land is now prolific, rolling, and lined with shadows of the past. Everything here germinates—plant, thought, relation.

The human presence on the island seems no less organic. The people do not appear imposed on the land but in continuity with it—grounded, soft-spoken, and attuned to its rhythms. With a population of about 250,000, São Tomé nonetheless generates a social atmosphere of expansiveness, shaped not by affluence but by affect. Hospitality is not a gesture here, but a condition.

Our guide for the day is a 20-year-old university student named Gervaciley Júnior. He is currently studying Taoist philosophy a field of inquiry that, though seemingly far from his local context, aligns seamlessly with the fundamentals of the island itself. The intellectual and spiritual poise with which he approaches the world signals not only personal maturity, but a worldview attuned to balance, interdependence, and ethical modesty.

He begins with an apology: “Forgive my English,” he says, smiling, “Portuguese is my first language, and I also speak French.” In the cramped minivan, we are nine tourists, nearly all monolingual. Yet within minutes, none of us are inclined to correct him as he requested. His speech is captivating not because of its polish, but because of its depth. He communicates with intellectual clarity and moral awareness. To interrupt would be to lose access to something rare.

“We are not rich in economy,” he tells us, “but we are rich in nature—our cocoa, our coffee, our birds, our trees, and the sea.” What might initially sound like a platitude is, in fact, a quiet reframing of what is important. He does not celebrate poverty, but neither does he accept that wealth must be measured in economic terms. His frame of reference is ecological, moral, and metaphysical.

What distinguishes Gervaciley is not only what he knows, but how he inquires. His questions do not seek to validate his own knowledge, but rather to invite collaboration. “Please,” he asks us, “tell me how I can speak better English. And tell me—what advice would you give my country? What can we do better? What should we focus on?” This is not rhetorical self-effacement. It is integrity.

When Gervaciley speaks about São Tomé’s colonial history, he doesn’t sound like a distant historian. Instead, he speaks like someone who’s been thinking deeply about what comes after, about how a country begins to live beyond its occupation. He explains that after independence, people didn’t rush back to work. They hesitated. Not out of laziness, but as a kind of quiet rebellion. After generations of forced labor, rest became something radical, a way for the body to reclaim its worth. Simply choosing to pause was, in itself, an act of freedom and an act of reclaiming narrative ground.

Later, along the undulating coast, I find myself turning his words over in my mind. What if, I begin to ask myself, the notion of labor as redemptive, so central to Western moral imagination, is not universal, but ideological? In São Tomé, as in so many postcolonial contexts, labor has been the site of dispossession rather than dignity.

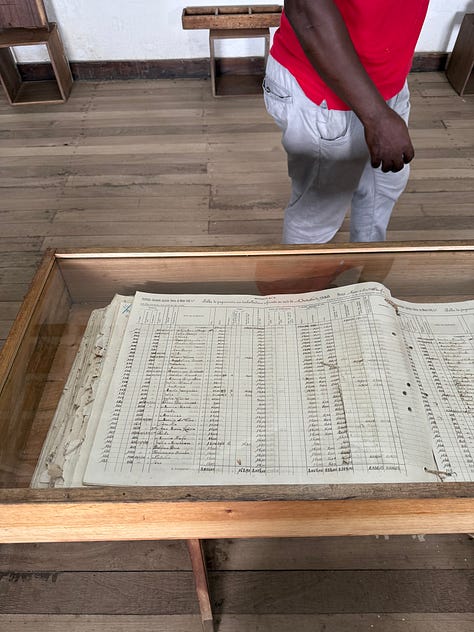

For the enslaved and the indentured servant, work was never a path to self-betterment. It was extraction. Their lives were logged in ledgers, each hour accounted for, and yet, at the end of the day, they were charged for food, shelter, and medicine by the very agents of their captivity. The result was not compensation but erasure. The arithmetic of injustice always balanced to zero, or worse, to generational debt.

This was not labor as craft or vocation. It was bodily depletion in service of someone else’s wealth. It was the loss of time with loved ones, the fracturing of kinship. Even after the formal end of slavery, the embodied memory remained, a suspicion that labor might still be betrayal in disguise.

We are accustomed to celebrating work as virtue, as identity, as moral scaffolding, as a contribution to the common good. But in São Tomé, Gervaciley makes visible another lineage, work as harm, as historical wound, as the residue of unfreedom. He does not speak of this with resentment. He speaks with precision. With presence.

As I think of Gervaciley, I realize that we travel not merely to observe the unfamiliar, but to interrogate the familiar, to recalibrate assumptions long held as universal by encountering the complexity of other histories. In conversation with difference, we discover our own frameworks—the notion of labor as virtue, the conflation of economic participation with moral worth, the assumption that one model of progress fits all contexts. These beliefs fracture under the weight of lived realities shaped by colonization, resistance, and cultural continuity. Speaking across distance—geographic, linguistic, historical—reveals that understanding is not achieved through explanation, but through relation. Gervaciley asks what his country might learn from strangers is not seeking affirmation but entering a space where mutual transformation becomes possible. In such exchanges, it becomes a dismantling of borders—inner and outer. It becomes a method, a form of inquiry, an ethical stance, and a reminder that knowing is not arrival but movement, flight—an openness to be undone and remade, and that wisdom is often carried by those least likely to be heard.

A thought-provoking piece.

Love it! What can I say? Just love it.