Around the world without flying

Danuta's Flights

Danuta’s note: One of the secret best parts of travel is the people we meet along the way—not only those rooted in the places we visit, but also the temporary neighbors whose cabins share our corridor for a month. On our Africa voyage we met Martin and his husband, Peter, and fell easily into that happy rhythm of shipboard friendship: meals that ran long, conversations that kept opening. Martin is a former BBC reporter; Peter is the kind of listener who makes a story grow in the telling. Very quickly, they felt less like fellow passengers and more like companions.

I keep wondering what makes that spark. Do we reach for the familiar—shared European backgrounds, a certain education, the comfort of overlapping references—or does difference do the inviting? Is kinship built on politics, faith, a taste for investigative journalism, or simply a mutual weakness for chocolate? Maybe it happens in the exchange of childhood stories, where remembering becomes a bridge; or in the way two people can predict the same future from different angles. Perhaps it’s simpler: attention meeting attention. In that spirit, I’m delighted to share Martin’s guest essay—a story about courage, ingenuity, and love made practical, told in scenes that remind us why slow travel enlarges the heart.

Around the world without flying

Martin Borley-Cox

It was a childhood dream to visit Australia and New Zealand. Being literally on the other side of the world gave them an other-worldly romance: Australia with its kangaroos, koalas, venomous snakes and spiders; New Zealand with its lush green hills, bubbling mud pools and mountains that smoked and shook.

At my Nottinghamshire primary school, we had a Kiwi teacher for a year. She told thrilling stories about Māori warriors who stuck out their tongues and she introduced us to earthquake drills — cowering under our desks while we pretended the ground was shaking. In retrospect, it was probably a clever classroom-management tactic.

Television back then was full of Australia too — most memorably Rolf Harris, before we learned the repulsive truth about him. In those “innocent” days he was a household name, painting sun-baked red landscapes, playing the didgeridoo, and singing about Six White Boomers pulling Santa’s sleigh across the outback.

My granny bought me my first single in 1969 — Two Little Boys — in which Harris sang about brothers fighting on opposite sides of a distant civil war. I couldn’t help but imagine what it would be like if it were me and my older brother. “But I think it’s that I remember,” the song went, “When we were two little boys.”

Decades later, when I confessed my still-burning desire to visit Australia, my husband Peter had a stock reply:

“I won’t stop you.”

“But I want to go with you!”

The snag? Peter has a severe and utterly debilitating fear of flying. Gin, tranquillisers, hypnosis, fear-of-flying courses — he’d tried them all. But logic never wins. A true phobia is when your body locks up at the aircraft door, when your nerves insist that physics is lying, and when your tears start before you even reach the airport.

Our last flight together, back in 2009, was an emotional ordeal. My dream of us touring Australia and New Zealand quietly fizzled out.

Instead, we became European travellers. We’d hop on a train at St Pancras and head for France, Spain, the Netherlands or Italy. We took the occasional cruise — the Baltic, the Greek islands — to reach places trains couldn’t. And sometimes I’d go solo: visiting relatives in Canada, a friend in New York, a wedding in Vegas. Life was good, if slightly clipped around the edges.

Then one day, out of the blue, Peter said:

“Let’s go to Australia and New Zealand.”

“Uh?”

“Let’s do it.”

To this day, I’m not entirely sure what changed. Perhaps it was a post-pandemic re-evaluation of life. Perhaps he’d reached a point in his career where he could take a break. It doesn’t matter. What mattered was that he’d said yes.

By then, I was hoping to retire — a good thing, as planning an around-the-world journey without flying takes time and the patience of a saint. Going overland via Russia and China would have been the obvious route — if Russia hadn’t invaded Ukraine. That left one option: a patchwork of trains, cars and ships.

Timing mattered too. To reach Australasia in time for summer, we’d need to leave Europe in early autumn. But a traditional round-the-world cruise wouldn’t work — they dash through Australia and New Zealand in a matter of days. We wanted weeks.

The other challenge was my health. I was born with a chronic lung condition and need mountains of medication. Would it really be safe to travel so far, and for so long? My hospital consultant didn’t hesitate: “You’ve only got one life—go and fill it.” It was exactly the permission I needed.

Bit by bit, we stitched together a route — a jigsaw of ocean crossings and overland sections. Then, just as it was coming together, Houthi rebels began attacking ships in the Red Sea, effectively closing the Suez Canal to cruise liners. Back to the drawing board.

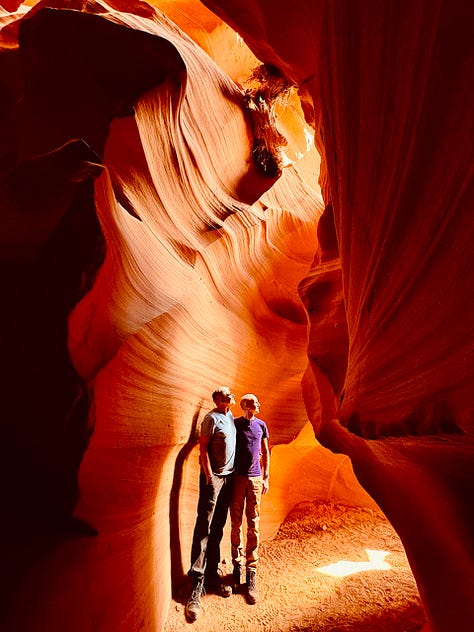

Our route now had to cross America and the Pacific, returning via Africa. Our nine-month odyssey became eleven. Thirty countries on five continents. We really would see the world — though in a series of vivid snapshots rather than a single, smooth journey.

Now that we’re home, it all feels slightly unreal — a blur of oceans, cities, deserts and faces, stitched together by chance and curiosity. We’ve seen wonders we could barely have imagined, met people whose kindness and stories have changed how we see the world, and proved that you don’t need wings to go anywhere. And as I think back to that old song, I realise that Peter and I, in our own way, were just two little boys again — wide-eyed, curious, and discovering the wonder of the world together.